Published in Board Leadership, vol. 178 – November-December 2021. Click here to subscribe to Board Leadership.

Board governance is not easy, nor should it be, when you consider the full scope and depth of accountability that boards have.

Boards navigating their way through the early stages of Policy Governance adoption might feel especially challenged, particularly as they move from a state of unconscious incompetence to conscious incompetence.

New terms like “legal and/or moral ownership,” “any reasonable interpretation,” “Executive Limitations,” and “Ends,” poke and prod at board members’ brains, demanding precision in usage.

Students of Policy Governance are also reminded again and again how all the principles used together comprise a system, and that “using parts of a system can result in inadequate or even undesirable performance. It is rather like removing a few components from a watch, yet expecting it still to keep accurate time.”1

As brilliant as the “watch analogy” is, some people new to Policy Governance wonder if the whole system concept is a bit too much to ask, or shrug their shoulders and take the extreme view that unless all 10 principles are perfectly applied all of the time, there is really no point in trying.

Those who have been applying Policy Governance principles for many years often make governance much more difficult than it needs to be by creating an accumulation of increasingly complicated layers of policies, practices, and procedures that might have been useful at one time, but no longer serve any meaningful purpose.

It’s understandable how this happens, as each newly comprised board seeks to elaborate and to improve upon the work of the preceding boards, adding some detail here, a process there, and then perhaps throwing in a spreadsheet and a few forms for good measure.

It’s this documentation and procedural build-up over many years that some people then equate to or confuse with Policy Governance, when the real requirements of Policy Governance are relatively simple.

As great as the challenge in governing that Policy Governance boards experience, boards using “traditional” governance approaches arguably have an even more difficult job. Spare some empathy for the board members who don’t know who they serve, what success looks like, how to express values as policy, or how to delegate. Right this minute, people are suffering through recurring conversations going nowhere, lengthy opinions on operational minutiae, committee reports that could have been circulated by email, arguments that have more to do with ego than the best interests of the organization, and on it goes. Imagine having no focus, no principles, no system at all.

Now, however, is no time to shrink from the challenge of effective governance. Boards, especially duly constituted public boards, are literally under attack. At school board meetings, for example, elected board members have come under vicious verbal and even physical assault from activists over mask and vaccine mandates, as well as other issues of the day.

Good governance is not an impenetrable shield against externally driven illegal, boorish, or nefarious acts, but it very well might help boards keep their hands steady on the wheel as they make their way through rough and stormy waters.

When times are tough enough already, board governance should not be made any more complicated or difficult than it already is. Board members need to be engaged and effective; not burnt out or running for the hills. With increasing threats to democracy, the need for wise and skillful board members to hold steady the wheels of public, private, and nonprofit institutions is greater now than ever before.

The good news for Policy Governance boards is that there are many ways they can streamline their processes while still remaining faithful to the principles. As a principle-based rather than a rules-based system, Policy Governance allows much more flexibility, scalability, and creativity than it is given credit for.

Let’s be clear: Policy Governance is not easy, but it can be a lot easier than people think. In our work with clients, we’ve seen two keys in accelerating results and sustaining momentum:

- Exhale.

- Do one thing.

By advising boards to exhale, we mean the necessity to let go of old processes, routines, behaviors, and even people who no longer contribute to the objective of “translating the wishes of owners into organizational performance.”2 Before boards can truly absorb and develop new habits, and take their performance to the next level (inhale), there are usually many activities they need to stop (exhale).

One of the biggest time-saving practices boards should stop is maintaining operationally focused committees as if they report to the board and not to the CEO. Certainly individual board members are free to volunteer to serve on operational committees (and the CEO or staff are free to reject their offer to volunteer), but continuing to pretend that these committees are board committees is no longer necessary within the framework established by the board’s new policy manual. If board members are concerned that relinquishing an operational committee will deprive the board of information it needs, then there are other ways of assuring the board that it will receive that information, without muddying the line of authority and accountability between board and CEO.

The board meeting agenda can also present a treasure trove of opportunities to exhale old practices so that new and engaging conversations can take their place. The presentation of reports is a common time-consuming element in traditional board meeting agendas, and it’s something we’re betting most people wouldn’t miss if it were eliminated or scaled back significantly.

Boards using Policy Governance will need to assess monitoring reports, and receive other reports related to the board’s governance function. But the presentation of operational information that does not trigger a decision by the board can be circulated at any time and need not be placed on a board meeting agenda.

Another practice boards can “exhale” while retaining Policy Governance principles is having a schedule or method for reviewing (as distinct from monitoring compliance with) all policies once per year or so. While reviewing Ends policies once per year is recommended, all other policies can be reviewed on an as needed basis, or certainly less frequently than once per year. The board can and should change policy language whenever it needs to; whether a regular routine similar to the monitoring schedule is desirable for doing so is completely up to the individual board.

We’ve found that boards can also save time in how they evaluate their own performance, i.e., their compliance with Governance Process and Board-Management Delegation policies. Ideally, whichever evaluation method a board uses will compare people’s actions with the criteria set out in policy, and give the board an increasing ability to align its behaviors with stated expectations.

Some boards, however, can get just a little bit too fancy with this self-evaluation process, creating much more paperwork, metrics, surveys, forms and the like than are really needed. If these kinds of processes are working ⏤ great! If not, boards can achieve similar results by scaling all the way back to a focused conversation during a board meeting, and noting the outcome(s) of the conversation in the minutes.

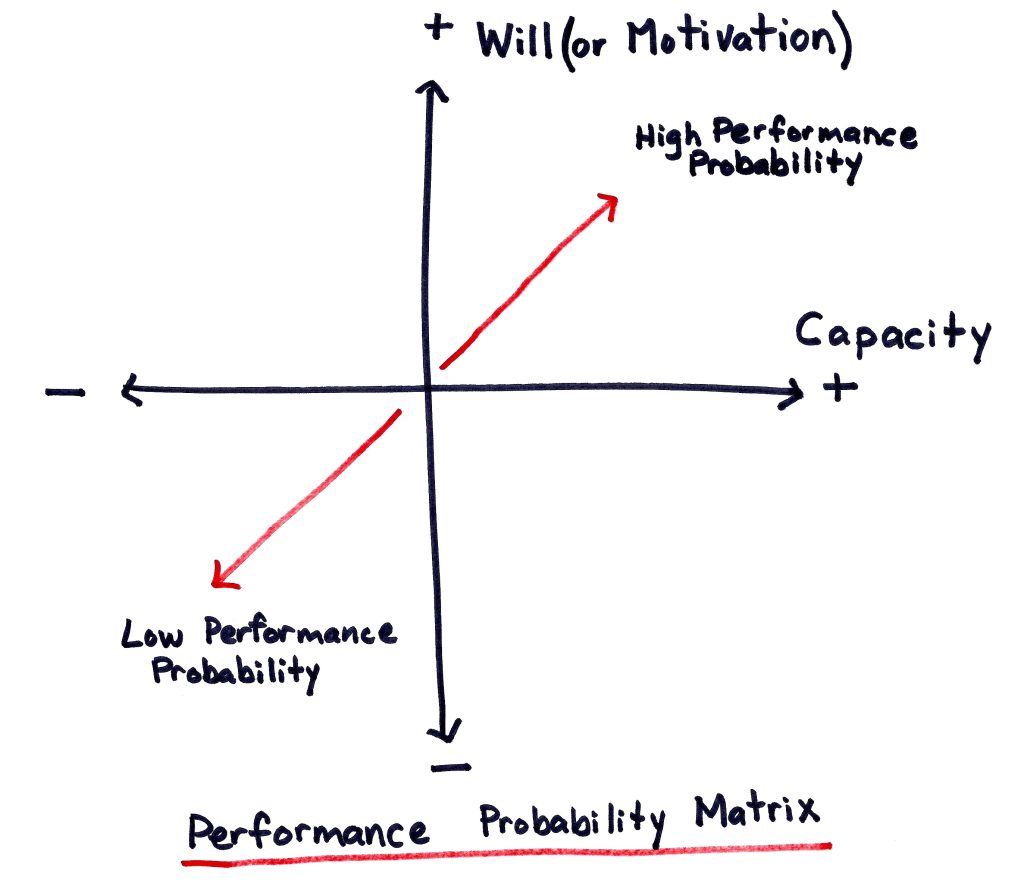

Lastly, it might be necessary to “exhale” certain board members or people who occupy board-appointed officer positions. This option is not always possible, and usually somewhat unpleasant, but if a board member or CEO is resisting the use of Policy Governance principles or accomplishment of the board policies themselves, they can be reminded that other options to contribute to the organization might be available. Excellence in governance requires both good people and good process; if lack of progress can be attributed to, for example, a Chief Governance Officer who has no will to fulfill his/her role, a Board Secretary who doesn’t attend meetings, or a Chief Executive Officer who doesn’t accomplish the Ends, then perhaps a change is in order.

The second key we promote to boards right now is to do one thing. It’s a common human desire to want perfection, to create comprehensive plans, and to get everything done all at once. In the early stages of adopting Policy Governance, some boards have a tendency to freeze, not knowing where to start, and wanting to do everything perfectly. The answer is simple: take one step. And when that’s done, take another.

If the challenge is getting started on ownership linkage, one simple step could be:

- brainstorm three questions the board will ask its owners;

- post a message to owners from the board on the website;

- schedule one focus group session (in person or online) to take place during the year;

- arrange to meet with another board that has many of the same owners;

- set aside time on a board meeting agenda to discuss all owner input received over the past year.

If the challenge is producing more engaging board meetings, one simple step could be:

- devote one board meeting to having a “What If” session3;

- re-format board meeting agendas to focus on (1) ownership linkage,(2) board education, (3) policy decisions, (4) monitoring;

- ask each board member to facilitate a board education topic of their choosing over the next year or two;

- invite a facilitator to guide the board through a difficult or controversial issue;

- create a “board meeting report card” for use by owners who view or attend board meetings.

In the best of times, governance is a skill that requires un-learning and re-learning, a commitment to serve, a willingness to listen, and a great deal of emotional intelligence. When times are difficult, and the ability of boards to provide wise, steady leadership is under threat, the need for speed in applying good governance principles rises in importance. By focusing on the essentials, and by executing one simple step at a time, boards will have a better chance of weathering the storm.

1Carver’s Policy Governance® Model in Nonprofit Organizations by John Carver and Miriam Carver, https://www.carvergovernance.com/pg-np.htm. This article was originally published as “Le modèle Policy Governance et les organismes sans but lucratif” in the Canadian journal Gouvernance – revue internationale, Vol. 2, nos. 1, Winter 2001, 30-48.

2John Carver, “Rethinking Governance Research,” John Carver on Board Leadership: Selected Writings From the Creator of the World’s Most Provocative and Systematic Governance Model (Jossey-Bass, 2002) 31.

3John Carver, “Is Your Board in a Rut? Shake Up Your Routine!,” Ibid., 380.